At 22, I enrolled in a doctoral program at a mega-university. The last week of the semester, I had what the school psychiatrist called a “nervous breakdown.” Although I finished the semester with As and Bs, I gave up the idea of completing a doctorate. I started teaching school.

I didn’t give up going to college, though. I returned to my small alma matter and enrolled in classes every semester until I had amassed more than sixty hours over the Master’s degree. I studied everything that interested me. Computer Programming. Advanced Childhood Psychopathology. Solfege. Belly Dancing. When I was at the top of my district’s pay scale for hours, I couldn’t justify continuing to pay tuition.

Fifteen years later, at a family reunion, I overheard my mother tell my cousin, “Please get Millie to finish the doctorate she started. It’s all her daddy and I are living for.”

Shit. Hellfire and damnation.

My cousin wasn’t about to lay that burden on me, but I’d heard my mom, so I decided I had to finish the degree. I could continue to teach my high school special education students and commute 176 miles three nights a week during the school year and daily in the summer to finish. Although I had way more than enough hours for a doctorate already, I would have to take thirty hours (mostly statistics and research classes) and complete qualifying exams and the dissertation process. I would need three years to do it.

I started the University of Arkansas in the first summer semester of 1989. I enrolled in Advanced Statistics I.

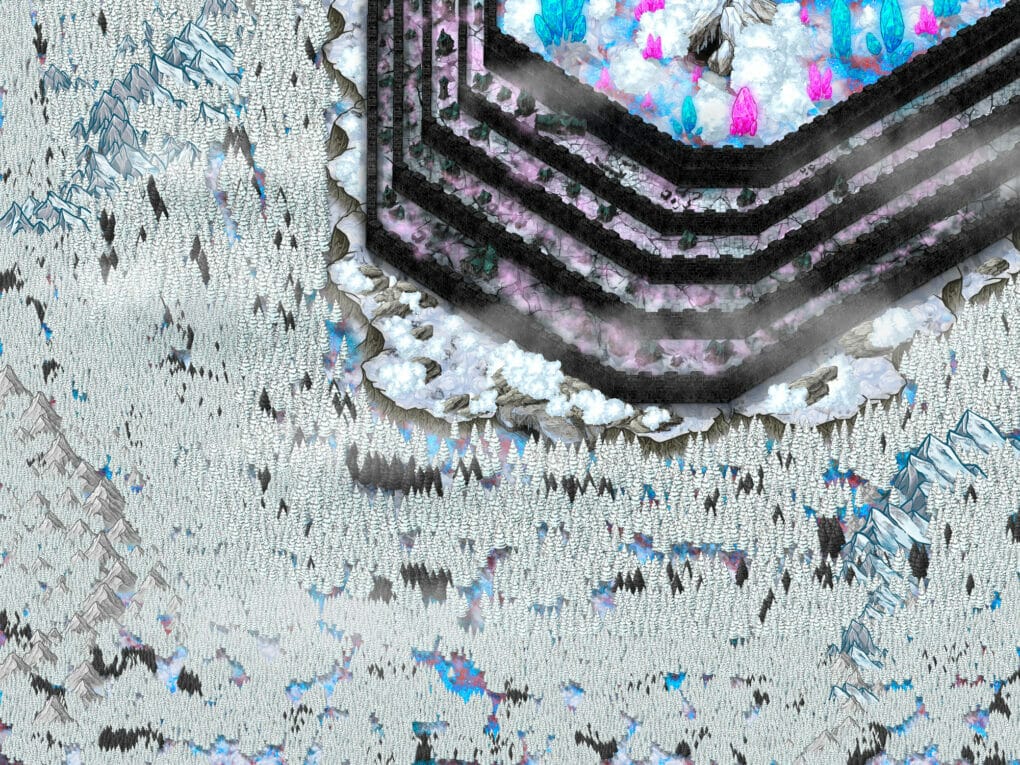

On my first drive to school, when I was climbing a steep hill to go through a narrow pass in the rugged Arkansas Ozark mountains, I began to pray, “God, if you will give me the physical and mental health to finish this degree, I will become a college professor and spend the rest of my life teaching people that love is the most important thing in the world.” Immediately, three eagles appeared overhead, soaring in the updraft of the pass. I named that spot Eagle Pass, and it became a sacred place to me.

By that time, I’d had enough heartbreak in my life to know that regardless of how smart you were, how hard you worked, or how faithful you were in serving God, if you didn’t have other human beings to love and who loved you, you didn’t have nuthin’.

I had learned that from my high school students, too. Yes, they needed the skills and knowledge to survive in the world of work, but I saw that they, like me, needed love more than anything else: the love of parents and teachers, the love of friends, and the love of that special young man or woman who quickened their step and made their eyes sparkle.

But I quickly learned that my expectations of doctoral school were all screwed up. It’s called a doctor of PHILOSOPHY, so I thought we would spend our time talking about what’s good, what’s true, what’s beautiful. About love. Nothing could have been farther from the truth.

I excelled in the first semester of Advanced Statistics, and I was sailing through the second semester (a go-to person for grad students who were struggling), yet I became increasingly sad. One morning when I drove up Eagle Pass and the eagles were soaring overhead, I said to myself, “The doctoral program is nothing like I expected. We don’t talk about what’s good, or true or beautiful. We don’t talk about love. All we talk about is statistics and research, statistics and research, statistics and research.”

I continued thinking about that as I finished my drive. When I pulled up to my college, for the first and only time ever, I found a parking spot right in front of my building.

I took it. Then I sat in the car. Eventually, I leaned my arms on the steering wheel, lay my head on my arms and began to cry.

“God,” I said, “I’ve made you a promise I can’t keep. I thought the doctoral program would be a place to learn about goodness and truth, beauty and love. But it’s not. All they talk about is statistics and research. I’ve made a terrible mistake. I told you that if you gave me the mental and physical health to do this, I’d spend my career teaching people that love is the most important thing in the world. But there’s apparently no place in college to talk about love. I’ve made you a promise I cannot keep.”

When I was cried out, I went to my statistics class, puffy-eyed. I sat down in my desk, first column, third seat back. The class filled up.

Right on time, our statistics professor, Dr. James Bolding, strode into the room and straight to the board. He started writing a long, complicated formula on it, the formula for the t-test for independent samples. Frantically, we copied it in our notebooks.

Halfway through the formula, he stopped. He turned around and stared at the class.

“Do you people know what the most important thing in the world is?” he asked.

Stunned at the question, nobody answered.

He repeated himself. “Do you people know what the most important thing in the world is?”

Still, we sat in silence.

Finally, gruffly, he said, “I asked you people a question. Do you know what the most important thing in the world is?”

“Statistics?” I asked timidly.

“No,” he said, “Love is the most important thing in the world.” Then he turned back to the board and continued writing his formula.

I nearly peed myself. I whispered, “Message received and understood. Thanks, God.”

Three years later, when I wrote the acknowledgments section of my dissertation, I noted, “… and to Dr. James Bolding, who taught me that love is the most important thing in the world.”

The day I defended my dissertation (which was on friendship, a form of love), he was the third professor to come out into the hall, shake my hand, and say, “Congratulations, Dr. Gore.” Then he said, “I have one question. Why did you write I had taught you that love is the most important thing in the world?”

I said, “That day, when you were teaching us the t-test for independent samples, and you turned around and looked at us and asked us what the most important thing in the world is, and then told us it was love.”

“I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about,” he said as he walked away.

That lesson has stayed with me, and in my career, I tried to teach my students in words and actions that love is the most important thing in the world, not “touchy-feelie” love, but love in the Pauline sense: doing what’s best for another person, even when you’d rather not.

In addition to special education, I became a professor of multicultural education/human diversity, and I came to understand how hard the lives of LGBTQI people could be. I began to teach about supporting the young children of same-sex parents and then adolescents who were coming out.

I was the first person ever to present at national and international education conferences about the importance of supporting gay and lesbian teenagers with disabilities- an exponentially marginalized group- in the coming out process. I am proud to say that all major special ed conferences now have this topic as a strand, and I know that I started it- little old me – because people began to understand how important the message was.

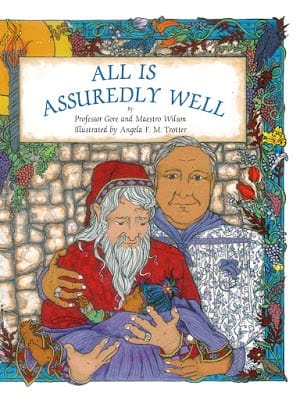

So now, in the late autumn of my life (I’m nearer 70 than 60), it’s time, as Professor Gore, to tell the world in another way that love is the most important thing in the world. It was the impetus for writing All is Assuredly Well, a picture book for the children of same-sex parents, and the six books in the series that will come after it: to show people through stories that love comes in many forms, and that nothing is more important than that. Yes indeed. Love is the most important thing in the world.

Oh. One last thing.

Thanks again, Dr. Bolding. May your spirit soar eternally with the eagles over Eagle Pass.

Title: All is Assuredly Well

Genre: Children’s Books

Publisher: Camille Lancaster Literary Children’s Books

All is Assuredly Well is available as an ebook and print at Amazon.com.

About the Author, Professor Gore

Professor Gore’s proudest hours were spent in Federal Court testifying as an expert witness and plaintiff against the city she loved. The city commission had passed an amendment that banned Heather Has Two Mommies and Daddy’s Roommate from the children’s section of the public library. A storyteller, Professor Gore is delighted to contribute to the canon she once defended.

meter lend themselves well to the lyrical art of storytelling.

Artist Angie F. M. Trotter holds a BA in Religion and Fine Art. Her pen and ink illustrations are an amalgamation of icons, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass window design, and her spiritual life. Her work has been compared to the masters of the Golden Age of British book illustration.

Come by Lacey’s blog and read her interview with Professor Gore, one of the authors for All is Assuredly Well as well as with the illustrator of the series, Angie F. M. Trotter.http://www.coffeewithlacey.

Come by Jessica’s blog where Professor Gore will be a guest writer and will be talking about how a workshop on screenwriting made her a better story writer.http://wolfdreamer25-

July 22nd @ Just a Place to Drop My Thoughts

Stephanie will be reviewing Professor Gore & Maestro Wilson’s book All is Assuredly Well. Come by and see what she thought about this impactful book!

July 23rd @ Cassandra’s Writing World

Check out Cassandra’s blog to find out her thoughts on Professor Gore & Maestro Wilson’s book All is Assuredly Well. Professor Gorewill also be discussing her thoughts on why attending conferences and workshops are worth the money (and how to make the best use of your time at one).

July 24th @ Author Anthony Avina Blog

Come by Anthony Avina’s blog where he shares his thoughts on Professor Gore & Maestro Wilson’s book All is Assuredly Well.

July 26th @ Author Anthony Avina Blog

Check out Anthony Avina’s blog where he will be sharing Professor Gore‘s guest post on why she

selected Maestro Wilson as her co-author and how they worked together.

July 27th @ The Faerie Review

Come by Lily Shadowlyn’s blog The Faerie Review where she reviews the book All is Assuredly Well.

July 30th @ Books and Motivation

Come by Prakash Vir Sharma blog and read his interview with author Professor Gore.

July 30th @ The Faerie Review

Come by Lily’s blog where author Professor Gore writes about fighting academic freedom after a student complained about ProfessorGore‘s class material about LGBQT class material.